|

The Lost Leader

|

| Michael Collins. 1890-1922 |

Of all the many rebel leaders who shine out of Irish History only one

stands out as a really effective revolutionary: Michael Collins. Except for his short public career he was too busy with practical

matters to concern himself with social ideas, he was a sort of Irish Lenin. He took hold of a potentially revolutionary situation

in Ireland and made it work.

Michael Collins was born in Sams Cross, Co. Cork in the year 1890, the youngest

of eight children. His father, Michael Collins senior was 76 when he was born. He was educated in nearby Clonakilty. At the

age of 16 he went to London and worked in the Post Office Savings Bank in West Kensington. While in London he was highly active

in the Irish Clubs and Organisations. These included the then recently founded Gaelic League, designed to promote the use

of the Irish Language, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) which promoted the Irish games of Gaelic Football and Hurling

and the Irish Volunteers While in London he also joined the secret Irish nationalist group, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

(IRB). The IRB believed in the creation of an Irish Republic, by armed force if necessary. He was sworn into the IRB by Sam

Maguire, a West Cork Protestant whose name was later to grace the Cup for which county Gaelic Football teams in Ireland were

to play for. He had no intention however, of joining the British Army, and when it was rumoured in 1916 that Irishmen of serving

age, living in Britain, would be conscripted, he left for Ireland where conscription had not been introduced.

Easter Week and Internment: As a member of the Irish Volunteers Collins

participated in the Easter Rebellion as aide-de-camp to Joseph Plunkett. Reflecting on the rising later, he showed his contempt

for anything impractical. Despite the fact he would not have regarded himself as socialist, he showed a clear preference for

James Connolly, the socialist leader of the rising than for Patrick Pearse, a more traditional nationalist. He wrote: "Of

Pearse and Connolly, I admire the latter most. There was an air of earthly directness about Connolly. It impressed me. I would

have followed him through hell had such action been necessary. But I honestly doubt very much I would have followed Pearse

- not without some thought anyway." Following the Rising, he was interred in Stafford Jail and later Frongoch in North Wales.

Along with many in Frongoch, he reflected on the rising and concluded that the attempt to seize strategic strongpoints and

hold them in the face of vastly superior odds had been a bad mistake. In future the tactics would be based on those of deVet

in South Africa during the boer war-hit and run. This was an important departure for the IRB who had hitherto held onto the

view that Ireland would be liberated in a giant rebellion, rather like the American Civil War. Collins, along with most of

the rebels was released in December 1916.

The election of 1918,

the creation of Dail Eireann and the start of the War of Independence saw Collins combine a number of roles. He was Minister

for Finance for Dail Eireann and in that capacity raised a huge loan for the work of the Dail and then placed it into bank

accounts that the British were never able to trace. He was also elected President of the IRB, and used that body for contacts.

Most famously however, he became Director of Intelligence for the Irish Volunteers and used his contacts in Dublin Castle

to great effect. In September 1919 he set up "the Squad", a group of volunteers that would kill G-division men and others

considered dangerous to the volunteers. Their most famous coup was the killing of 14 British Officers involved in intelligence

work (nicknamed the Ciaro Gang) on Bloody Sunday. All of this Collins achieved while on the run. The British considered him

so important that they put a price of stlg10,000 on his head. Collins however, seldom bothered to disguise himself and moved

from meeting place to meeting place in Dublin on a bicycle. He knew well that the British were hampered by the fact that they

had no good photographs of him and relied on poor descriptions. He joked and chatted with British police and soldiers at checkpoints

around the city.

As the War of Independence raged on Collins' escapades became

better known and he came to represent the elusive enemy to the British. The Black and Tans raided houses in Dublin shouting

"where is Michael Collins? We know he sleeps here!" The public delighted in the evident inablility of the authorities to catch

him. As time went on sections of the British public and establishment developed a grudging admiration for the Irish leader.

Lloyd George is said to have exclaimed "Where was Michael Collins during the Great War (World War One)? He'd have been worth

a dozen brass-hats (British Generals)!" The War of Independence continued with the IRA conducting raids and ambushes on British

Barracks and convoys such as those at Kilmichael. The Black and Tans and the Auxies conducted sweeps throughout the country

in an attempt to find their elusive enemy such as that at Crossbarry. The IRA, despite their numerical inferiority had the

benefit of a supportive population and considerable growing sympathy abroad.

By mid-1921 the two sides

had fought themselves to a virtual stalemate. On the one hand it was clear that it was impossible for the IRA to defeat the

British militarily. A fact brought home to Collins when the IRA suffered disastrous losses in the raid on the Customs House

in May 1921. The IRA was also running dangerously short of ammunition. On the other hand however, the British realised that

military victory for them was no closer; the IRA remained as elusive as ever. British public opinion was more hostile towards

Government policy on Ireland than ever before and Sinn Fein's support was as high as ever in Ireland. The speech of King George

V at the opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament allowed Lloyd George to open the door to negotiations and a military truce

was agreed.

After initial talks in London deValera

announced his team for negotiations. Contraversially, it included Collins who was reluctant to go, saying that he was a soldier

not a diplomat. He also made the case that it would be better if he was in Dublin so that the delegation could use him to

gain further concessions from the British by saying that he wouldn't accept the agreement. The fact that during the negotiations,

he, the most wanted man in Ireland, would be photographed by the Press from every angle probably weighed on him as well. Collins

however, eventually agreed to go, accepting de Valera's request. Equally contraversially, De Valera said that he would not

go and that Arthur Griffith would lead the delegation instead.

During the negotiations,

the two major sticking points were firstly, whether the new state would be a Republic or a Dominion of the British Empire

and secondly, what would happen to Northern Ireland. Collins felt that the IRA were close to defeat and the prospect of going

back to war weighed heavily on him as a result. Like Arthur Griffith and Eamonn Duggan, he felt that if given substantial

freedom in the treaty, it could be built upon and could mean a Republic in future years. He saw the treaty, not as an end

in itself but as a "stepping stone" to greater things in the future. The other members of the delegation however, such as

Robert Barton and George Gavin Duffy were more Republican and believed that assurances could be given to Britain on defence

without necessarily joining the British Empire. After lengthy negotiations, on December 5th 1921, the British gave the Irish

a deadline to accept or reject the treaty. Rejection would mean "immediate and terrible war" in the words of Lloyd George.

Upon returning to their hotel Griffith, Collins and Duggan agreed they would sign and after much soul searching Gavin Duffy

and Barton (despite urgings from Erskine Childers) agreed to sign in the early hours of December 6th. Writing to a friend

later Collins said "Think, what have I got for Ireland? Something she has wanted these past seven hundred years. Will anyone

be satisfied at the bargain, will anyone? I tell you this, early this morning I signed my death warrant, I thought at the

time, how incredible, how fantastic, a bullet may well have done the job six years ago. These signitures are the first real

step for Ireland. If people would only remember that, the first real step."

The treaty debates were bitter

and exposed divisions within Sinn Fein that had existed prior to War of Independence but only now had the opportunity of being

seen in public. Collins, in particular was attacked, the image of Collins as the elusive IRA leader had aroused jelousy and

clearly the treaty allowed many to release considerable pent-up resentment at the popular leader. Seamus Robinson said that

Collins's reputation for great deeds "existed only on paper" and asked that "is there any authoritative record of his ever

firing a shot at an enemy of Ireland?" Cathal Brugha who opposed the treaty and clearly resented the influence of Collins

over the IRA, which he, as Minister for Defence was nominally in charge of, said that Collins was "a subordinate in the Department

of Defence" whom the press had made "a romantic figure such as this gentleman certainly is not." Countess Markievicz said

that Collins would marry Princess Mary and become the first Governor General of the Free State. This didn't impress Collins

who recently got engaged to Kitty Kiernan, a Longford woman. The treaty was passed by 64 votes to 57. De Valera resigned and

put himself forward for re-election, he was defeated by 60 votes to 58.

Collins and De Valera did their

best from their respective positions to prevent the slide towards Civil War. De Valera, however, was hampered by the need

to keep the die-hard Republicans in line and accordingly had to sound more extreme than he actualy was. Together they agreed

the Pact but when elections took place, the anti-treaty side fared poorly, the electorate was broadly in favour of the treaty,

of that there was little doubt. The firing on the Four Courts by Free State guns signalled the start of general warfare throughout

the country. Collins and De Valera did their best from their respective positions to prevent the slide towards Civil War.

De Valera, however, was hampered by the need to keep the die-hard Republicans in line and accordingly had to sound more extreme

than he actualy was. Together they agreed the Pact but when elections took place, the anti-treaty side fared poorly, the electorate

was broadly in favour of the treaty, of that there was little doubt. The firing on the Four Courts by Free State guns signalled

the start of general warfare throughout the country.

Faced with the reality of Civil War, Collins threw himself into the task

in hand with gusto. He reorganised the army and became the Commander in Chief of the Free State forces. The death of his old

friend Harry Boland depressed him considerably as did the death of Arthur Griffith. He returned to Dublin from a tour of inspection

in Cork to attend Arthur Griffiths funeral and returned to Cork immediately afterwards. He was also attempting to find a negotiated

end to the Civil War by talking to neutral IRA officers. On the 22nd of August 1922, while returning to Cork his convoy was

ambushed by anti-treaty forces. During the firing, Collins was killed, he was the only fatality on either side in the ambush.

Upon hearing the news Richard

Mulcahy, the Army Chief of Staff issued a note to all members of the Army "Stand calmly by your posts. Bend bravely and undaunted

to your work. Let no cruel act of reprisal blemish your bright honour. Every dark hour that Michael Collins met since 1916

seemed but to steel that bright strength of his and temper his gay bravery. You are left each inheritors of that strength."

Republican prisoners in Maryborough jail (now Portlaoise prison) knelt and prayed when they heard the news. Erskine Childers,

the anti-treaty sides chief propagandist, himself to die shortly afterwards, praised him and outside De Valera's headquarters,

the tri-colour flew at half mast.

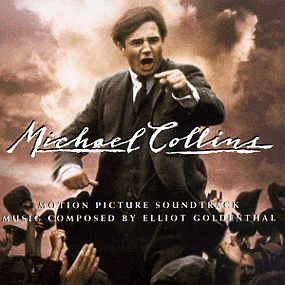

The Film

|

| Liam Neeson as Michael Collins |

|

|

|

music playing: Fire and Arms,

from the soundtrack of

Michael Collins

Easter Rebellion -

Fire and Arms

Train Station Farewell

Winter Raid

Elegy for a Sunday

Football Match

On Cats Feet

Defiance and Arrest

Train to Granard

Boland Returns (Kitty's Waltz)

His Majesty's Finest

Boland's Death

Home to Cork

Civil War -

Sinéad O'Connor

Collins' Proposal

Anthem Deferred

She Moved Through the Fair -

Sinéad O'Connor

Funeral/Coda

Macushla

|

| Michael Collins. 1890-1922 |

|

| Harry Boland, Michael Collins and Eamon De Valera. |

Irish Patriot. 1890-1922

Commander-in-Chief,

Irish Free State Army.

|

| Michael Collins' Funeral cortege |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Film images are TM & © 1996 Warner Bros. and Geffen Pictures. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|